We may earn a commission from links on this page. Learn more

Since ancient times, man has been interested in anatomy — how muscles and bones function and fit together and how the body works. But it wasn’t until the Renaissance that the study of anatomy really took off, thanks in large part to the printing press, which helped anatomists, illustrators, scientists, and physicians get on the same page (pun intended).

In 2010, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, hosted an exhibition titled, “The Body Inside and Out: Anatomical Literature and Art Theory.” It is from Smithsonian Magazine’s short profile of the exhibition that I draw the following quote:

The relationship between artists and physicians during the Renaissance (roughly 1300 to 1600) was symbiotic. Artists like Michelangelo and Leonardo Da Vinci, who were interested in exacting the human form in their art, observed physicians at work to learn the layers of muscle and bone structures that formed certain parts of the body. In turn, physicians contracted artists to draw illustrations for the high volume of texts coming out in the field of anatomy, made possible by Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press around 1440. Some artists even forged partnerships with specific physicians (Titian and Andreas Vesalias [sic] are perhaps the best-known example), in which the physicians would allow the artists to assist in dissections (highly restricted at the time) in exchange for anatomical drawings and illustrations.

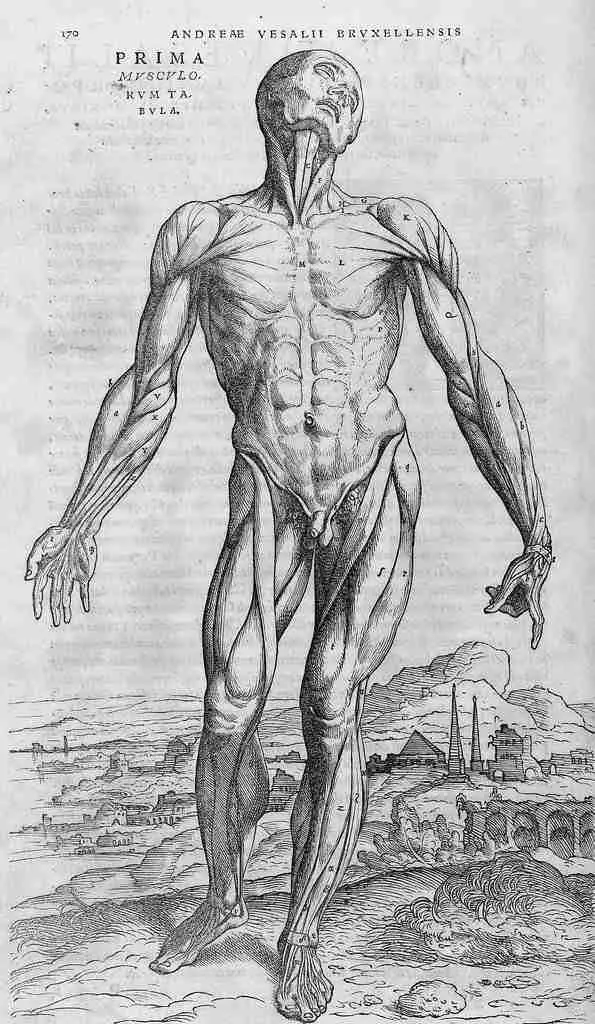

Born in Belgium, Andreas Vesalius is best known for his De humani corporis fabrica (On the Fabric of the Human Body), a first-of-its-kind, seven-volume illustrated text on human anatomy published in 1543. Although Vesalius published his magnum opus in Basel, Switzerland (where a Vesalius-dissected skeleton is still on display), he researched, wrote, and commissioned woodcut illustrations for his work while studying and lecturing at the University of Padua. A superstar scholar-turned-chair of surgery and anatomy at Padua, Vesalius challenged long-held beliefs about anatomy by harvesting and dissecting human bodies himself.

Vesalius and the artist-anatomists who came before and after him benefited from the more relaxed laws (no laws?) in the Italian peninsula concerning anatomical research vis-a-vis cadaver usage and its historical advancements in the study of the human form for artistic purposes. For example, about a half-century before Vesalius, artist Antonio Palloaiuolo, according to Giorgio Vasari, “had a more modern grasp of the nude than the masters before his day, and he dissected many bodies in order to study their anatomy.”

Leonardo da Vinci, who died when Vesalius was five years old, is one of the best known artist-anatomists, having created many anatomical sketches throughout his storied career. Then, of course, Michelangelo and Luca Signorelli, are famous for their detailed paintings of the human form, its musculature and movements.

Around 1537, the Belgian Vesalius came to Padua, then an already important university town of the Venetian Republic, to study for his doctorate in medicine and earned the chairmanship of Padua’s Anatomy and Surgery Department upon graduation, thanks to his hands-on approach to this fascinating but gruesome field.

Mary Roach, author of the book Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers, described Vesalius as an “avid proponent of do-it-yourself, get-your-fussy-Renaissance-shirt-dirty anatomical dissection.”

“Vesalius was a dissector such as history had never seen. This was a man who encouraged his students to ‘observe the tendons while dining on any animal.’ While studying medicine in Belgium, he not only dissected the corpses of executed criminals but snatched them from the gibbet himself.”

Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers by Mary Roach

Vesalius’s main motivation for snatching freshly dead bodies and cutting them up was to understand—and contradict—the teachings of Galen, an early Greek physician whose theories about human anatomy were accepted as fact, even though Galen had only carried out dissections on animals. In addition to doing the dirty work of dissecting human cadavers, Vesalius also began making detailed drawings of his findings, a project that won him acclaim and notoriety in Padua, Bologna (where he occasionally lectured), Venice, and beyond. He soon found an ally in a criminal court judge in Padua, who made sure Vesalius “had a steady supply of cadavers from the gallows.” The steady supply allowed Vesalius to do enough research to create his seven-volume Fabrica, a book that made him and the University of Padua famous.

Through hands-on dissection, a technique that earned him as many fans as detractors, Vesalius laid the foundations for our understanding of the systems of the body (skeletal, muscular, nervous, vascular, circulatory) and some of its major organs. Following Vesalius, who died in a shipwreck in 1564, was his erstwhile student and successor Gabriele Falloppio, whose work on women and female cadavers led him to discover the “trumpets of the uterus” (the Fallopian tubes), coin the term “vagina,” and develop the world’s first condom. Falloppio’s successor as chair of the anatomy department at Padua was Hieronymus Fabricius ab Acquapendente, who built the world’s first permanent anatomical theater in 1594 at the University of Padua’s Palazzo Bo.

The anatomical theater at Palazzo Bo, which was built around a central, oblong operating slab and could accommodate 250 spectators in its wooden galleries, was used for instructional autopsies from its inauguration in 1595 until 1872. The theater is still preserved and open to visitors. Guided tours of the Palazzo Bo, which include the anatomical theater, the Aula Magna (the great hall where Galileo once lectured), and other architectural and artistic features, are open to the public.

Lesser known is the anatomical theater at Palazzo Archiginnasio, formerly the main building of the first university in Europe—the University of Bologna. Anatomy department scholars in Bologna, who had also been influenced by Vesalius, built an anatomical theater at the school shortly after the permanent one in Padua was built. But the one that visitors can see at Bologna’s Biblioteca Comunale dell Archiginnasio, is a post-WWII reconstruction of a permanent one installed here in 1636. The anatomical theater and lecture hall (Stabat Mater) at Palazzo Archiginnasio are open to visitors for a small fee. But the entire palace, which houses the city library, is worth a detour. Take a virtual tour of Palazzo Archiginnasio to learn more.

The Book That Fixed Anatomy: De Humani Corporis Fabrica by Andreas Vesalius | Patrick Kelly

This month’s Italy Roundtable theme was “harvest.” Read what others have written on the topic:

- Jessica – A Little Stardust Caught

- Rebecca – Digging for Umbria’s Black Gold: Truffles

- Alexandra – Olive oil tours in Tuscany

- Kate – My favourite festival: Harvest

Last Updated on 2 years ago by Melanie Renzulli | Published: October 22, 2015