It’s one thing to get excited about €1 homes in Italy in villages you’ve never heard of. And it’s quite another when the village in question is one you know very well.

I recently stumbled across the news that the tiny town of Biccari in Puglia (Apulia) is jumping on the cheap home bandwagon in order to bring in new life to this sleepy mountain town. Biccari Mayor Gianfilippo Mignogna is offering a number of turnkey, ready-to-move-in properties for approximately $9,000. It’s a wise strategy in order to lure would-be residents who are turned off by the daunting task of renovating an old or dilapidated property.

But here’s the thing — Biccari is the ancestral home of my mother-in-law. So I have some misgivings about this new scheme. On the one hand, I am nervous about a horde of tourists descending on this small town and disrupting the calm. On the other, I wonder how new residents would cope living in this insular, isolated place.

I have spent a lot of time in Biccari. I’ve visited Biccari in every season, during holidays and festivals as well as when nothing has been going on.

I’ve been there on sweltering afternoons waiting for something (anything!) to open up. The Biccaresi honor the siesta like no place I’ve ever been, shuttering homes and businesses at noon and not reopening until 4 p.m., sometimes 5.

Closer to Molise in geography and spirit than it is to the beach resort towns of its region, Biccari sits among woodlands, expansive valleys of wheat, and smooth hills dotted with industrial windmills. It sits in the shadow of Monte Cornacchia, the highest peak (1,151 meters) in Puglia. “These are mountain people,” my husband likes to point out when trying to explain how his mother and her family were very different than the caricature of ebullient and chatty southern Italians.

Like many places in small-town Italy, Biccari is liveliest on the feast day of its patron saint San Donato. The early August festival brings a lot of former residents back to town, many lingering for days or weeks before and after the event before returning to their homes in Milan, Turin, Naples, Germany, Canada, the United States, and elsewhere.

On the day of the feast — August 7 — many Biccaresi, accompanied by a hired marching band, parade through the town with statues of San Donato and other saints. (This type of religious celebration, of big, shoulder-borne processional structures, has been recognized by UNESCO as an intangible cultural heritage.)

Meanwhile, the rest of the residents watch the procession from their stoops or balconies. When night falls, there’s a big concert on Piazza Matteotti and fireworks. It’s a fun time, but it’s gone in a flash.

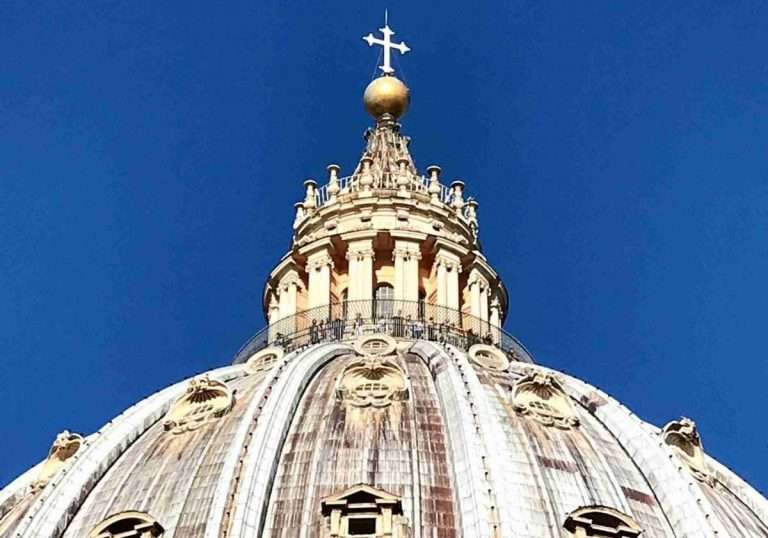

Though Biccari is lovely, defined by the elegant dome of Saint Mary of the Assumption, the 12th-century Byzantine Tower, and well-maintained cobbled squares, it is beset by many of the problems endemic to the Mezzogiorno. A lack of jobs led many Biccaresi, including my mother-in-law and her family, to seek opportunities elsewhere.

Getting to Biccari also isn’t so easy. It is accessed by slow, often poorly maintained, provincial roads. The nearest train station is in Foggia, about half an hour away. And Foggia isn’t even well-connected to rail. It takes nearly three hours to get to Foggia on the fastest routes from Rome, Naples, or Lecce, and requires at least one change. In other words, if you wish to live in Biccari, you will need a car.

When my family has visited Biccari, we have usually opted to stay in nearby hotels (of which there are few) because the home in town is very small. Most of the houses in the heart of the village are very small and modest, the size of small apartments, and without air conditioning.

My mother-in-law’s childhood home is located on one of the main streets in the center of town, ideal for walking to church or to the main square. But it is tiny — one large room comprised of the kitchen, dining room, and living room; a bedroom about the size of a king-sized bed; and a bathroom with barely enough room for a toilet and shower. It is unfathomable to me how she once lived here with her parents, her five brothers, and their animals (which stayed indoors in a small storage space at the back of the room).

I write this post not to discourage folks from considering a move to Biccari, but to paint a picture of what I have seen and experienced in this town. I have mixed feelings because I want Biccari to succeed in trying to repopulate its town. But I also want to give a reality check to people who may not consider some of the small details and logistics when moving to small-town Italy. I suppose that what I have described above could be said about many of the towns that have offered these unbelievable deals to foreign investors. A lot of these towns are losing residents because village life is hard.

But who knows what could happen? Perhaps this could be the beginning of Biccari’s rebirth into a destination. The Basilicata town of Matera, approximately two hours south of Biccari, transformed itself from a poor, sunbaked town of cave dwellings into a magnet for artists and tourists. It took many decades, but Matera eventually earned the spotlight as the European Capital of Culture in 2019. Given Biccari’s small size, it won’t be able to follow the same path as Matera. But it could become a Calcata or Cervara.

I spoke briefly last night with my mother-in-law about the Biccari news. And while she was delighted to see her hometown’s name in the international press, she also had a wry smile when she asked me if I wanted to move there. “It’s a nice place to visit,” I said diplomatically, “but I don’t think I could do it full-time.” She nodded via FaceTime from her condo in Florida.

Last updated on May 19th, 2021Post first published on February 3, 2021

![Gabbiano Azzurro Hotel & Suites: Sardinian Style in Golfo Aranci [Review]](https://www.italofile.com/wp-content/uploads/Pool-Terrace-Gabbiano-Azzurro-Sardegna-scaled-768x512.jpg)