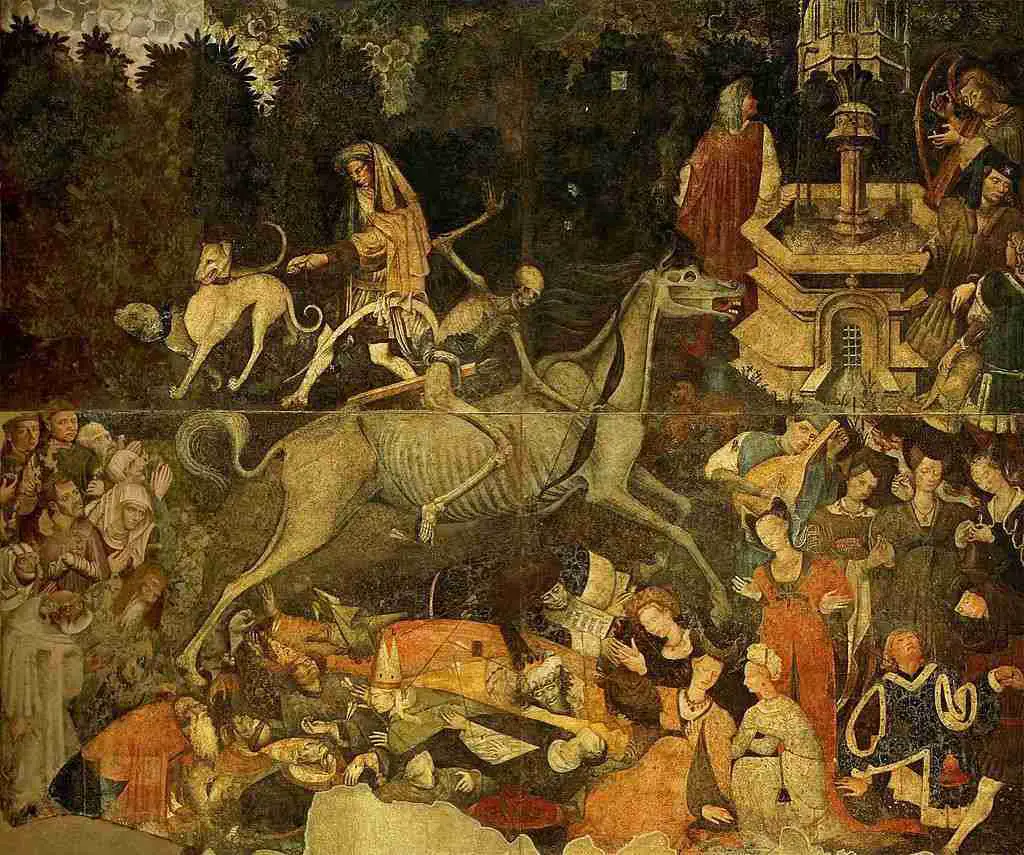

Throughout the long, lonely months of our modern pandemic, I’ve been thinking about a dark and mysterious painting in Palermo known as “The Triumph of Death.”

Known in Italian as Il Trionfo della Morte, the painting hangs in Palazzo Abatellis, a regional gallery in the Kalsa quarter of the Sicilian capital.

Measuring 6 m x 6.42 m (19.7 ft x 21 ft), the massive, detached fresco is housed in a domed hall, once part of a 16th century chapel, and is one of the first works of art you will see shortly after stepping inside the palace courtyard.

“The Triumph of Death” is also viewable from a balcony, which is where I took this photo that emphasizes its scale:

Depictions of Death

The fresco, which dates from circa 1446, depicts death as a human skeleton, equipped with scythe and quiver, atop a skeletal horse — a horseman of the apocalypse, if you will — galloping over and toward men and women, including the rich and the powerful. “Death bursts astride a skeletal steed,” reads the description on the Palazzo Abatellis website, “ready to shoot deadly arrows on noble pleasure-seekers and elegant ladies who, unaware, entertain themselves around the fountain of youth. At the margins, popes, emperors, sultans, monks and lawyers lie on the ground, already hit by arrows.”

In his article on “The Triumph of Death,” archaeologist Patrick Hunt explains how the macabre subject matter was a common theme at this time:

“Plague in the Middle Ages was a constant specter of death for much of the population for centuries, especially in the Mediterranean where ports were the point of entry for plagues in many kingdoms. Sicily was no exception, one of the first places where the pandemic bubonic ‘Black Death’ of 1347-51 reached, possibly killing 50% or more of urban population.”

In other words, “Triumph” is a sort of large-scale memento mori, a reminder of the inevitability of death and a theme seen in so many works of art across Italy, from churches and tombs to paintings from the Renaissance and the Baroque.

Mysterious Origins

The portraits of dead bodies upon bodies, of town folk making merry unaware that death is on its way, are in themselves strange and dark. And then there are references to the Black Death, a pandemic that had decimated Europe less than one century prior.

“At lower left is a mysterious group,” explains Hunt in his very detailed article on “The Triumph of Death.” “Some interpretations posit that this group is imploring Death to end their suffering, but the hypothesis suggested instead here…that they are plague survivors: Death has ridden by and they have been left apparently visually unscathed with no arrows protruding from them. It is possible that plague completely swept by them for whatever reasons.”

However curious the composition may be, the biggest mystery surrounding “The Triumph of Death” is the question of who the artist was.

The painting originally hung in the Palazzo Sclafani, an abandoned 14th century palace that was converted into the Ospedale Grande e Nuovo, Palermo’s first public hospital.

Sicily at the time was under control of King Alfonso of Aragon. So, many art historians, including Hunt, have speculated that the work could have been painted by Antonio Pisanello of Pisa and Rome and/or Gaspare Pesaro of Sicily, who were known to have worked as artists for the king. Other 15th century artists connected to the fresco include Antonio Crescenzio, Guillaume Spicre, and even Sicily’s best known artist Antonello da Messina (whose “Our Lady of the Annunciation” also hangs in Palazzo Abatellis).

But no one knows for sure. More than 500 years have passed and historians are still unable to confirm who painted the great fresco. But rather than list the artist as “anonymous” or “unknown,” historians often call him the “Master of the Triumph of Death.”

Why Does This Painting Looks Familiar?

This particular painting of “The Triumph of Death” is rarely mentioned among Italy’s great masterpieces. Which is strange, because it is believed to have inspired one of the most famous paintings of the 20th century.

Take a look at the central figure of “The Triumph of Death” and of “Guernica,” one of Pablo Picasso’s most important creations, painted in 1937. Though centuries and artistic styles separate these two paintings, the snarling, breathless horse at their center unites them.

It is not out of the question that Picasso, a Spaniard, was familiar with “The Triumph of Death.” After all, Sicily had been under Spanish rule for hundreds of years.

According to The Sicilian Post, “the [Sicilian] artist Renato Guttuso, who was a good friend of Picasso, in an essay entitled The Great Sicilian Equalizer (1986) and dedicated to the painting in Palermo, affirmed: ‘Once I had a talk about it with Picasso. He knew this fresco by illustrations but hasn’t ever seen it personally.'”

The conversation between Picasso and his good friend Guttuso was confirmed by the latter’s adopted son, Fabio Carapezza, and Cesare Brandi, who was present when the restored work was unveiled to the public in its new home in 1953.

Contemplating Plagues Past and Present

It’s hard not to be haunted by a painting titled “The Triumph of Death.” Even when I visited Palazzo Abatellis in the years before our current pandemic, I was moved by the chaos and sheer size of the composition as well as the horrors that it portrayed.

Writing for Palermo Viva, Saverio Schirò reminds us that the great canvas of “The Triumph of Death” was originally commissioned for Palazzo Sclafani, at the time a hospital for the city’s indigent. “Those who would have crossed that hospital courtyard would thus have received a consoling message: he was not a wretch for his social condition, since not only the poor, but everyone is destined for this passing while the world out there continues to perform the ordinary matters of life.”

At the time of my visit to Palermo and the Palazzo Abatellis, I could not even contemplate a comparable pandemic happening in my lifetime, a plague that killed widely and indiscriminately. I thought that another such calamity could not happen because of our technology, our medical advancements, and our modern understanding of how diseases are spread — through germs, through respiratory particles, through contagion and filth.

But bacteria also continue to evolve, even while humans and nations become complacent — another example of not connecting the dots, of history repeating itself. Now that we’re here, all we can do is wait and listen to a 500-year-old painting that is trying to speak to us.

Last updated on May 4th, 2021Post first published on November 24, 2020